Local lore in the Gurnee area claims that witches were burned at the stake in the early days of its settlement. Although this is one of the most far flung stories I've ever heard, it intrigued me enough to do some digging.

As it turns out, the untrue tale of a witch hunt in Warren Township hints at a very real connection to the mass hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

During the winter of 1691-1692 in Salem, Massachusetts, Elizabeth "Betty" Parris (aged 9), Abigail Williams (aged 11), Ann Putnam, Jr. (aged 12), Elizabeth Hubbard (aged 17) and Mercy Lewis (aged 17) became afflicted with fits "beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect."

At the time, the cause of their symptoms was very clear: witches in league with the devil.

Today, some believe the symptoms were a result of psychological hysteria due to Indian attacks on the colonists. Others have pointed to the possibility of rye bread made from grain infected by a fungus. Historians, however, believe that jealousy and revenge over land disputes motivated the accusations and that the girls were play acting (and enjoying the attention).

Whatever the cause, it resulted in twenty townspeople (14 women and 6 men) being accused of witchcraft and executed by hanging (one man was pressed to death). Among the accused were the three Towne family sisters: Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Cloyce and Mary Easty (Esty), who were targeted by the powerful Putnam family.

The 71-year old Rebecca Towne Nurse was accused in March 23, 1692, and hanged on July 19. The Nurse family had been in bitter land disputes with the Putnam family, who were her accusers.

Mary Easty's main accusers were also connected to the Putnams: Daughter, Ann Putnam, Jr. and their house servant, Mercy Lewis. At Mary Easty's examination on April 22, 1692, the girls feigned fits. When Easty clasped her hands together, Mercy Lewis imitated the gesture and claimed to be unable to release her hands until Easty released her own.

Easty's convincing manner in court and good standing in the community got her released from jail, but only for a couple of days. While most of Mary's accusers had backed down from their claims, Mercy Lewis fell into violent fits upon Easty's release, claiming that Easty was tormenting her.

A second warrant was issued for Mary Easty and she was again brought before the court. This time with more witnesses against her. She was thrown in jail with her younger sister Sarah Cloyce, and together the two women composed a petition to the magistrates asking for a fair trial. Despite the eloquent petition, Mary was tried and convicted on September 9, 1692. (Sarah Cloyce remained in jail for eight months, but was given a reprieve and escaped execution).

The day of her execution on September 22, Mary made a final statement: "The Lord above knows my innocency... if it be possible, that no more innocent blood be shed..."

She was hung with seven others on Gallows Hill and together they were called the "eight firebrands of Hell."

In 1706, Ann Putnam, Jr. publicly apologized for her role in the witch trials. "I desire to be humbled before God... I, then being in my childhood... made an instrument of the accusing of several people for grievous crimes... now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons."

In 1711, the Easty family was given 20 pounds in compensation for Mary's wrongful execution.

Fast forward to over a century later, when in 1836 - 1837, Mary Easty's great-great-great grandsons, Avery Esty and Moses Esty left Massachusetts to settle in Warren Township, Lake County, Illinois.

In 1842, just a few years after the Esty's settled here, Proctor Putnam migrated to Warren Township. He was the g-g-g-grand nephew of Mary Easty's accuser, Ann Putnam, Jr.

Once again, the Towne/Esty and Putnam families lived within a few miles of each other. This time much more peaceably.

Though a thousand miles from their ancestors' painful pasts, it seems the families roles in the Salem Witch Trials came to light. Over the decades, the truth of those distant events morphed into witches run amuck in Gurnee.

Perhaps we can blame it on a bit of tainted rye bread.

As it turns out, the untrue tale of a witch hunt in Warren Township hints at a very real connection to the mass hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials of 1692.

During the winter of 1691-1692 in Salem, Massachusetts, Elizabeth "Betty" Parris (aged 9), Abigail Williams (aged 11), Ann Putnam, Jr. (aged 12), Elizabeth Hubbard (aged 17) and Mercy Lewis (aged 17) became afflicted with fits "beyond the power of Epileptic Fits or natural disease to effect."

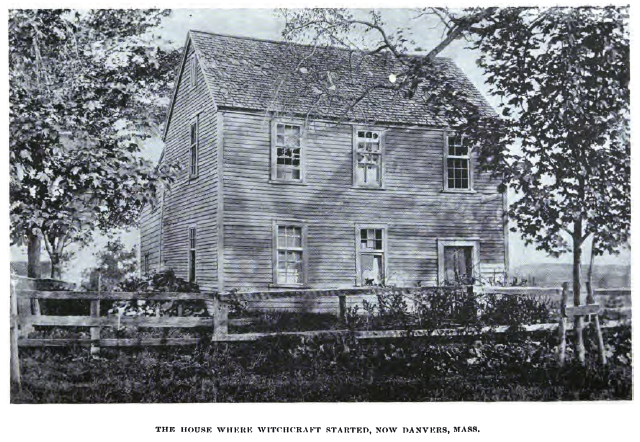

|

| The Samuel Parris house, Salem Mass. (now Danvers, Mass.) known as the "House where witchcraft started." Two of the main accusers, Betty Parris and her cousin Abigail Williams lived here. |

Today, some believe the symptoms were a result of psychological hysteria due to Indian attacks on the colonists. Others have pointed to the possibility of rye bread made from grain infected by a fungus. Historians, however, believe that jealousy and revenge over land disputes motivated the accusations and that the girls were play acting (and enjoying the attention).

Whatever the cause, it resulted in twenty townspeople (14 women and 6 men) being accused of witchcraft and executed by hanging (one man was pressed to death). Among the accused were the three Towne family sisters: Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Cloyce and Mary Easty (Esty), who were targeted by the powerful Putnam family.

|

| Statue of the three Towne sisters accused during the mass hysteria of the Salem Witch Trials, 1692 |

Mary Easty's main accusers were also connected to the Putnams: Daughter, Ann Putnam, Jr. and their house servant, Mercy Lewis. At Mary Easty's examination on April 22, 1692, the girls feigned fits. When Easty clasped her hands together, Mercy Lewis imitated the gesture and claimed to be unable to release her hands until Easty released her own.

|

| Depiction of the Salem Witch Trials, 1692. |

Easty's convincing manner in court and good standing in the community got her released from jail, but only for a couple of days. While most of Mary's accusers had backed down from their claims, Mercy Lewis fell into violent fits upon Easty's release, claiming that Easty was tormenting her.

A second warrant was issued for Mary Easty and she was again brought before the court. This time with more witnesses against her. She was thrown in jail with her younger sister Sarah Cloyce, and together the two women composed a petition to the magistrates asking for a fair trial. Despite the eloquent petition, Mary was tried and convicted on September 9, 1692. (Sarah Cloyce remained in jail for eight months, but was given a reprieve and escaped execution).

The day of her execution on September 22, Mary made a final statement: "The Lord above knows my innocency... if it be possible, that no more innocent blood be shed..."

She was hung with seven others on Gallows Hill and together they were called the "eight firebrands of Hell."

|

| Bench marker for Mary Easty at the Witch Trials Memorial, Salem, Massachusetts. Families of the dead reclaimed their bodies after dark and buried them in unmarked graves on family property. |

In 1711, the Easty family was given 20 pounds in compensation for Mary's wrongful execution.

Fast forward to over a century later, when in 1836 - 1837, Mary Easty's great-great-great grandsons, Avery Esty and Moses Esty left Massachusetts to settle in Warren Township, Lake County, Illinois.

|

| 1861 Warren Township plat showing the Moses Esty property (west of Hunt Club Road and north of Grand Avenue); and Proctor Putnam property (Washington Street and Milwaukee Ave). |

In 1842, just a few years after the Esty's settled here, Proctor Putnam migrated to Warren Township. He was the g-g-g-grand nephew of Mary Easty's accuser, Ann Putnam, Jr.

Once again, the Towne/Esty and Putnam families lived within a few miles of each other. This time much more peaceably.

Though a thousand miles from their ancestors' painful pasts, it seems the families roles in the Salem Witch Trials came to light. Over the decades, the truth of those distant events morphed into witches run amuck in Gurnee.

Perhaps we can blame it on a bit of tainted rye bread.